West Medina Mills

The River Medina was one of the main trade routes onto the Island for many centuries and was the ideal place for the growing industries nurtured by the Industrial Revolution (c 1770 to 1820s).

Two tidal mills had been built on both sides of the River Medina in the late 18th Century and in 1791, the West Medina Mill at Dodnor was sold to William Porter, a miller and meal man who sold pies in Newport. Unfortunately, construction of the West Medina Mill ceased in 1793, when Porter lost his life savings when a partner at his bank in Newport absconded abroad with all of the bank’s money.

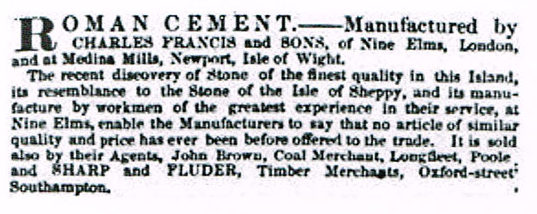

After a varied history of use as barracks for the military based at Parkhurst and as storage space for local merchants, the site was sold to Charles Francis and sons in 1841.

Charles Francis was a Victorian entrepreneur who went into partnership with John Bazely White to make cement at their Nine Elms factory in Wandsworth in and by 1825, Francis and White had become the leading makers of a “Roman” cement which set underwater.

By 1836 Francis and Whites partnership was dissolved and Charles Francis went into business with his sons and moved the enterprise to the West Medina Mills site which Charles Francis and Sons bought in 1841. The River Medina proved to be an excellent source of the “Septaria” stones from which Roman cement was made, as well as providing the tidal power of the old mill and easy access to the sea for delivery of the finished cement.

At first Charles Francis and sons continued to make the Roman-type cement from stones dredged from the River Medina. The cement it produced proved to be much harder than normal Roman cement and was called “Medina Cement”. Medina Cement was highly prized and won prizes at several exhibitions, including the bronze medal in 1851, the Gold Medal at both the Havre Exhibition in 1868 and the Paris Exhibition in 1875.

Charles Francis retired in 1852 at the age of 75 and his two sons continued to produce cement until they separated and the eldest, Charles Larkin Francis went into business with his own son, Henry, at the Dodnor site as Francis and sons.

We think that a new, more improved type of cement, called “Portland Cement” was made at the West Medina Mills site in the early 1850s. This was made from chalk which was ground in a mill and then mixed with clay and water in a wash-mill to produce a wet, thin “slurry.

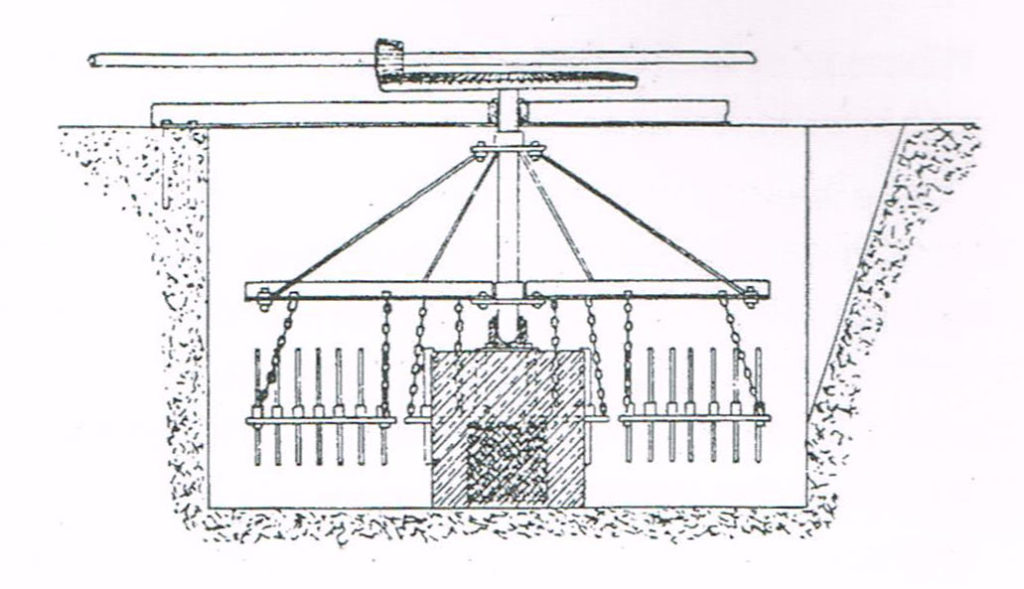

A typical 19th Century washmillThe slurry flowed into large drying reservoirs called “Slurry backs” in which the solids sank to the bottom and the water was drained off gradually until it was dry enough to dig out in lumps and taken by wheel barrow to the “Drying Floors” where it was heated from below until it was dry enough to be fired in the kilns.

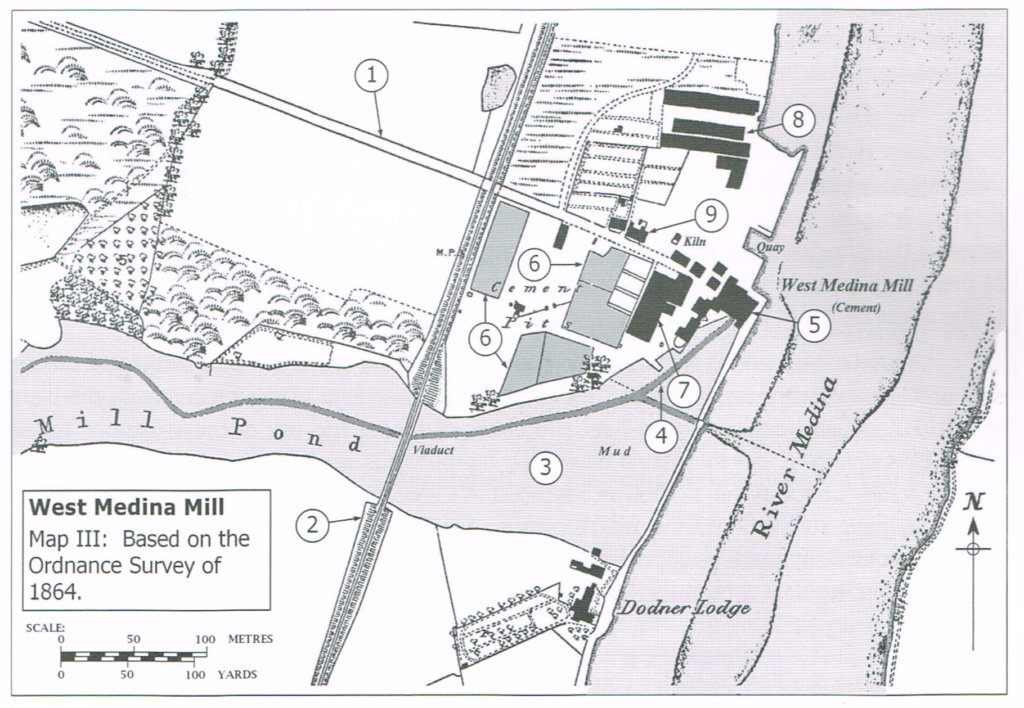

The 1st edition OS map, surveyed in 1864, shows the different parts of the West Medina Cement Mills factory. Stag Lane (1 on map) and the railway (2) which went over the mill pond (3) by a viaduct are clearly marked, as are the mill (5) and the slurry backs (6). The drying floors and banks of kilns are shown at no 7 and numbers 8 and 9 show the stores and other works buildings with cottages for some of the more senior workers.

The Company looked after its workers by providing an annual meal at a local hostelry, rowing matches were held and they even had their own cricket team called the “Black Mills”.

Although the raw materials of clay, chalk and coke were initially shipped in from Hamble and Fawley in Southampton Water, Francis and Sons soon began to dig the clay local clay from pits just to the west of the factory site and to bring chalk from the Shide chalk pit.

The cement factory hit hard times in the 1870s as advancing technology required fresh capital and technical expertise which were hard to find. The situation was not helped by the discovery that the firm’s book keeper had been embezzling money and by 1871 the company was bought by two gentlemen to become Charles Francis, Son and Company.

This change saw an increase in workforce from 100 in 1868 to 150 by 1873. This was also the time when the new more efficient Chamber Kilns replaced the Bottle kilns for making cement.

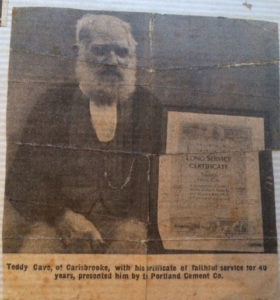

At least 2/3 of the workforce were local and the Cement Mill was an important employer in Northwood and Parkhurst for over 100 years. Workers at the West Medina Cement Mills had a variety of different jobs and we know of several who received their long service awards for working from the ages of 12 to 65.

Ted Cave of Carisbrooke, who is an ancestor of one of our archaeological excavation volunteers, was awarded his long service certificate for 40 years working for the company. We know that he was a night-foreman and a night tester.

William Jeffry retired after 42 years with the company in 1893 and can be seen in the photograph.

Different jobs around the site ranged from quarry men who worked the chalk from Shide chalk pit, to chemists, cement testers, mariners taking raw materials and finished cement on barges, to carpenters, coopers, sack repairers and even a “tally-boy”. Men loading the kilns worked stripped to the waist to combat the heat and drank a mixture of oatmeal in water to try and protect them against the noxious fumes. The fired clinker was drawn from the kilns whilst it was red hot and it was back-breaking work with each kiln burning for days. The men were paid by results so if a firing was unsuccessful, their wages were reduced.

By 1894, the company was managed by James Lovell Warsap and changes were made which increased the profitability at the cement factory. The company finally came to an agreement with the railway company for a tunnel to be dug under the railway to allow access to the clay pits to the west. In addition, the railway siding into the chalk pit at Shide was built. These two changes allowed the company to stop importing raw materials from the mainland and to use the local Island resources to their full extent.

In 1899, a devastating fire destroyed part of the original mill building, despite the heroic actions of the local firemen. By the 1890’s the cement manufacturers nationally were not prospering due to a huge fall in trade with Europe and America and in 1900 twenty four cement companies, including Charles Francis, Sons and Co joined to become the Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers Ltd. In the 1920’s this became Blue Circle.

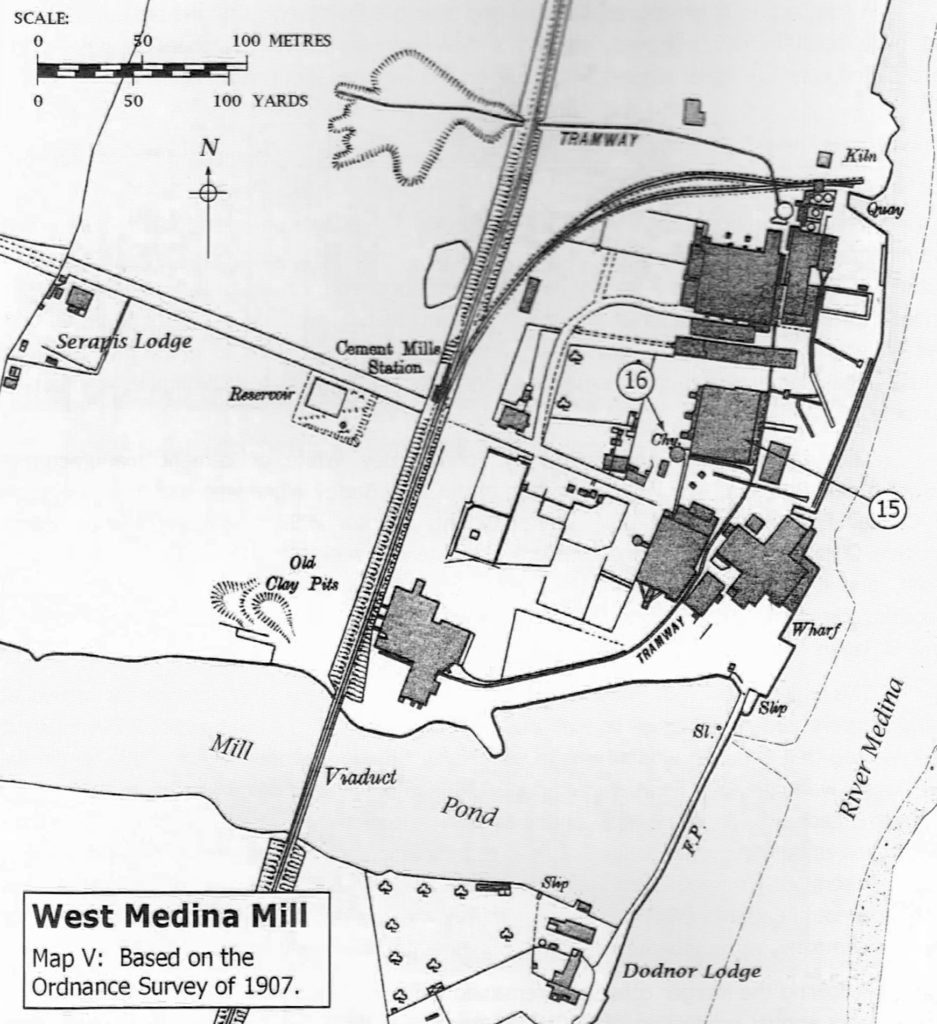

New kilns were developed and gradually the old chamber kilns at Dodnor were replaced with a Schneider Kiln (number 16 on map) in the early 1900s and by a Rotary Kiln in 1911. Cement continued to be made up to 1939 at the West Medina Mills site, but after World War II the site became a supply and distribution depot.

For almost a century, West Medina Mills Cement factory made and exported cement to many parts of the world and was an important part of the economic and social landscapes of the Isle of Wight. If you live in one of the many house built on the Island between 1840 and 1940, it is likely that your house contains cement made at West Medina Mills.

After production stopped the site became a bagging and distribution centre. We know a lot about this time because we have been given a lot of information by Dave Warne, a former driver there; and Richard Chase, grandson of Fred Chase, also a lorry driver. You can read all about this on our ‘Cement Stories’ page. The boat opposite is MV Ferrocrete.

After production stopped the site became a bagging and distribution centre. We know a lot about this time because we have been given a lot of information by Dave Warne, a former driver there; and Richard Chase, grandson of Fred Chase, also a lorry driver. You can read all about this on our ‘Cement Stories’ page. The boat opposite is MV Ferrocrete.

The information about the West Medina Mills Cement works has been taken from Alan Dinnis’ 2016 book called “West Medina Cement Mill, Dodnor, Isle of Wight: a history”. Alan is the grandson of James Lovell Warsap who was the manager of the West Medina Cement Mills between 1894 and 1929 and his book is a very well researched and fitting tribute to all of the people who worked at this site which was such an important part of the landscape of the River Medina for over a century. You can buy a copy of the West Medina Cement Mill book from WJ Nigh and sons, a local Island publisher in Shanklin.